If you were not familiar with Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), it’s likely that you have heard about it now – and not in a good way. Unfortunately, SVB on Friday became the biggest bank to fail since the global financial crisis in 2008. Since then, the Federal Reserve, U.S. Treasury, FDIC, and even larger banks stepped in to ensure liquidity, calm depositors, and stabilize markets. While it may be an appropriate time to revisit whether you have enough FDIC coverage for your money held at a bank (more on that later), the consensus view is that the overall banking system is well capitalized and has ample liquidity.

So how did SVB fail? SVB held long-term bonds that had lost significant value as the Fed hiked rates. In order to meet withdrawals from its accounts, SVB had to sell these bonds at a loss. As the bank came under stress, more depositors withdrew funds. This required SVB to sell additional holdings at a loss – and the cycle fed on itself until regulators stepped in to close the bank down. The bank had a heavy concentration of start-up and technology-related firms among its depositors and customers. So not only did the bank suffer from tightening liquidity and rising rates, but its customer and depositor base did as well. This was a major contributor to why other banks have not experienced the dramatic bank run, and failure, that SVB did. Exposure to concentrated areas of the market have proved to be detrimental to other banks: Silvergate Capital and Signature Bank of New York recently shut down after their heavy participation in the crypto space caught up with them.

Contagion is when a disturbance, like SVB failing, spreads within the financial system. Even during last week’s panic – and certainly after the reassuring announcements on Sunday – this risk is considered to be low. Why? SVB, Silvergate, and SBNY had concentrated exposure and limited entanglement with other financial institutions. This was unlike the large banks in the lead-up to the global financial crisis. In 2008, there was significant financial exposure between giant banks via complex securities, so one bank’s losses quickly turned into a threat for the whole industry.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) ensures that depositors at banks will receive any insured funds. On Friday, depositors at SVB did not know whether they would recoup any of their money above the FDIC limits. Regulators have since stepped in to shore up confidence in the banking sector: all customers of the failed SVB have access to their money today and other banks that might experience heightened withdrawals will have easier access to liquidity (borrowing from the Federal Reserve).

A Brief Review of FDIC Coverage

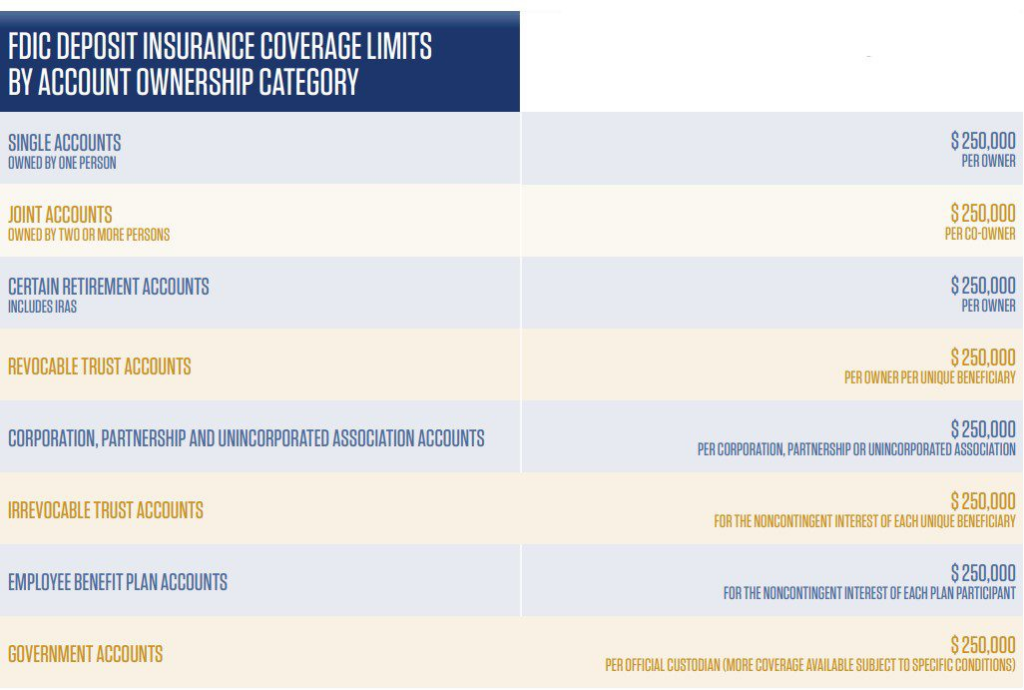

While the FDIC, U.S. Treasury Department, and Federal Reserve have quickly stepped in to support depositors beyond the traditional FDIC limits and likely would do this for other banks that came under duress, there is no guarantee. As such, one step you could consider taking is to spread out any bank balances in excess of FDIC limits, if any, to other banks (or new account types at the same bank). See the below chart as a reminder of FDIC insurance limits. Remember that all of these limits below are per bank.

Example 1: if Tim opens an individual account at five different banks, each of them is insured for up to $250k ($1.25M total).

Example 2: if Tim has an individual account and a joint account with Jenny at the same bank, the individual account is insured for up to $250k and the joint account is insured for up to $500k for a total of $750k. They could replicate these accounts at a second bank and double their total FDIC coverage.

Cash at TD Ameritrade and Schwab has always been allocated to a FDIC insured deposit account where the funds are held at one or more banks. These deposits are insured by the FDIC up to $250,000 per account, per bank.

Please contact us if you have any questions about the SVB failure or restructuring your bank accounts to increase FDIC coverage.